1. Defining objectives

We can start by asking ourselves the question: What are materials supposed to do? In defining the purpose of the materials, we can identify some principles that will guide us to the actual writing of the materials.

a. Materials provide a stimulus to learning process.

Good materials don’t teach but rather encourage learners to learn.

Good materials contain:

· Interesting text

· Enjoyable activities

· Opportunities for learners to use their knowledge and skills

· Content which both learners as well as teacher can overcome

b. Materials help to organize the teaching-learning process.

By providing a way through the complex mass of the language to be learnt. Good materials should provide a clear and understandable unit structure that will guide teacher and learners.

c. Materials contain a view of the nature of language learning.

Good materials should truly reflect what you think and feel about the learning process.

d. Materials reflect the nature of the learning task.

Materials should try to create a balance outlook that both reflects the complexity of the task, yet makes it appear manageable.

e. Materials can have a very useful function in broadening the basis of teacher training.

By introducing teachers to new techniques.

f. Materials provide models of correct and appropriate language use.

This is a necessary function of materials, but it is all too often taken as the only purpose, which the result is the materials become simply a statement of language use rather than a vehicle for language learning.

1. A materials design model

a. Input

This maybe a text, dialogue, video-recording, diagram or any piece of communication data, depending on the needs you have defined in your analysis.

The input provides a number of things:

· Stimulus material for activities

· New language items

· Correct models of language use

· A topic for communication

· Opportunities for learners to use their information processing skills

· Opportunities for learners to use their existing knowledge both of the language and the subject matter

b. Content focus

Language is not an end in itself, but a means of transferring information and feelings about something. Non-linguistic content should be exploited to generate meaningful communication in the classroom.

c. Language focus

Our aim is to enable learners to use language, but it is unfair to give learners communicative tasks and activities for which they do not have enough language knowledge. In language focus, learners have the chance to take the language to pieces, study how it works and practice putting it back together again.

d. Task

The ultimate purpose of language learning is language use. Materials should be designed to lead towards a communicative task in which learners use the content and language knowledge they have built up through the unit.

These four elements combine in the model as follows

· The primary focus of the unit is task

· The language and content are drawn from the input and are selected according to what the learners will need in order to do the task.

· It follows that an important feature of the model is to create coherence in terms of both language and content throughout the unit.

· This provides the support for more complex activities by building up a fund of knowledge and skills.

3. A material design model: sample materials

The basic model can be used for materials of any length. Every stage can be covered in one lesson, if the task is a small one, or the whole unit might be spread over a series of lessons. In this part, we will show what the model looks like in practice in some of our materials.

This material is intended for lower intermediate level students from a variety of technical specialism. The topic of the blood circulation system can be of relevance to a wide range of subjects. Apart from the general interest that any medical matter has, the lexis is of a very basic type that is generally applicable both literally and metaphorically (e.g. heart, artery, pump, collecting chamber, oxygen). Really, there are only two specific terms used, such as ventricle and auricle. So, the text is rather viewed as an illustration of the general principles of fluid mechanics than as a medical text.

As the unit title indicates, language is approached through an area of content. The topic represents a common form of technical discourse – describing a circulatory system – although in this case, presented from an unusual point of view.

The starter plays a number of important roles:

a. It creates a context of knowledge for the comprehension of the input. Comprehension in the ESP classroom is often more difficult than in real life, because texts are taken in isolation. In the outside world a text would normally appear in a context, which provides reference points to assist understanding (Hutchinson and Water, 1981).

b. It activates the learners’ minds and gets them thinking. They can then approach the text in an active frame of mind.

c. It arouses the learners’ interest in the topic.

d. It reveals what the learners already know in terms of language and content. The teacher can then adjust the lesson to take this into account.

e. It provides a meaningful context in which to introduce new vocabulary or grammatical items.

This section practices extracting information from the input and begin the process of relating this content and language to a wider context.

Steps 1 and 2 are not only comprehension checks. They also provide data for the later language work (step 5 and 6) this is an example of unit coherence.

Learners should always be encouraged to find answers for themselves wherever possible.

It is possible to incorporate opportunities for the learners to use their own knowledge and abilities at any stages. It is particularly useful to do this as soon as the basic information contained in the input has been identified, in order to reinforce connections between this and the learners’ own interests and needs. Here for example, the learners are required to go beyond the information in the input. They have to relate the subject matter to their own knowledge and reasoning powers, but still using the language they have been learning.

This section gives practice in some of the language elements needed for the task. These may be concerned with aspects of sentence structure, function or text construction. The points focused on are drawn from the input, but they are selected according to their usefulness for the task.

Further input related to the rest of the unit in terms of subject matter or language can be introduced at any point in order to provide a wider range of contexts for exercises and tasks. This helps learners to see how their limited resources can be used for tackling a wide range of problem (see also step 7).

Learners need practice in organizing information, as well as learning the means for expressing those ideas.

Earlier work is recycled through another activity. This time the focus is more on the language form than the meaning.

Language work can also involve problem solving with learners using their powers of observation and analysis (Hutchinson, 1984).

There is a gradual movement within the unit from guided to more open-ended work. This breaks down the learning tasks gives the learners greater confidence for approaching the task.

The unusual type of input gives the opportunity for some more imaginative language work.

Here the learners have to create their own solution to a communication problem. In so doing they use both the language and the content knowledge developed through the unit. The learners, in effect, are being asked to solve a problem, using English, rather than to do exercises about English. Given the build-up through the unit, the task should be well within the grasp of both learner and teacher.

The task, also provides a clear objective for the learners and so help to break up the often bewildering mass of the syllabus, by establishing landmarks of achievement.

The unit can be further expanded to give learners the chance to apply the knowledge gained to their own situation. For example, a project for this unit could ask the learners to describe any other kind of enclosed system (e.g. an air conditioning system) in their own home, place of work or field of study.

4. Refinging the Model

A number of possible refinements to the model can be seen in the unit above. We can relate these points to the nucleus of the model to provide an extended model like this:

Figure 30 : An expanded materials

model

5.

Materials and the Syllabus

In

chapter 7 we know although one feature might be used as the organizing

principle of syllabus, there are in fact several syllabuses operating in any

course. We have argued that the course design process should be much more

dynamic and interactive. We noted also when dealing with needs analysis in

chapter 5 that we must take account not just of the visible features of the

target situation, but also of intangible factors that relate to the learning

situation, for example learner involvement, variety, use of existing knowledge,

etc. A model must be able to ensure adequate coverage through the syllabus of

all the features identified as playing a role in the development of learning.

In addition to having an internal coherence, therefore, each unit must also

relate effectively to the other units in the course. There needs to be

coherence between the unit structure and the syllabus structure to ensure that

the course provides adequate and appropriate coverage of syllabus items.

Figure

31 illustrates in a simplified form how the unit model relates to the various

syllabus underlying the course design. Note, however, that identifying features

of the model with syllabus features does not mean that they only play a role in

that position, nor that other factors are not involved in that position. The

diagram aims to show the main focus of each element in the materials.

We

have made wide use of models throughout this chapter. At this point it is

useful to make a cautionary distinction between two types of model, since both

are used in the materials design process:

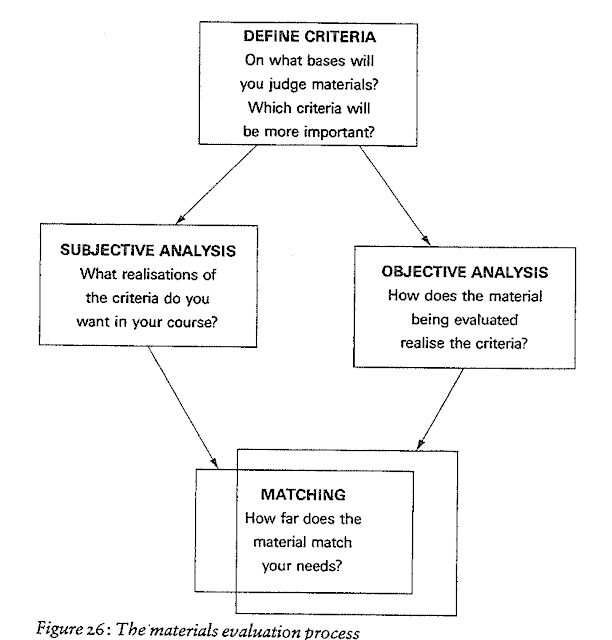

a)

Predictive.

This kind of model provides the generative framework within which creativity

can operate. The unit model (Figure 26) is of this kind. It is a model that

enables the operator to select, organize and present data.

a) Evaluative.

This kind of model acts as feedback device to tell you whether you have done

what you intended. The syllabus/unit interface model (Figure 31) is of this

kind. Typically it is used as a checklist. Materials are written with only

outline reference to the S/UI. Then when enough material is available, the S/UI

can be used to check coverage and appropriacy.

If the models are used inappropriately, the materials

writers will almost certainly be so swamped with factors to consider that they

will probably achieve little of worth.

6. Using

The Model:

A Case Study

There was a model of learning which has been presented

before. In this section, this will show how to use that kind of model. But

here, we found some difficulties, such as:

a.

The text is mostly descriptive so that

nothing students can do except reading and writing only.

b.

The text contains specific vocabularies

that only can be explained by realia. However it is not available in the ESP

classroom.

c.

Students don’t have general language that

is used to connect to the specific vocabularies.

The further need analysis is conducted to fix the

difficulties of the model. The results are:

a.

The general technical topic should be

explained to students in order to make students become able to connect to the

specific subject.

b.

The assumption of teacher if students know

nothing or little about a specific matters, but they only know some general

words about that specific matter.

c.

Connecting the specific subject to another

is useful. Teacher can connect the topic of a specific subject to another

subject that is more general to make it easier to understand and to teach a new

and specific knowledge.

After having the new results, for the revision of need

analysis there’re some guidelines to use the model of learning well. The

guidelines are:

a.

Stage 1

Stage 1 is a stage to find the text.

Here a good text to be a model is required to be occurred naturally, suit to

the students’ need and interests, ad it generates some exercises and

activities.

b.

Stage 2

Stage 2 is a stage to assess the

text. The purpose is to assess the potential of the text to be a classroom

activity.

c.

Stage 3

In stage 3 we have to go back to the

syllabus and think about the match of the task. Is it a kind of activity that

will useful for the learners?

d.

Stage

4

Decide the language structure,

vocabulary, and functions that appropriate to the task and useful for the

learners. Here we identify name of parts, present active, etc.

e.

Stage 5

Think about the exercises to practice

the items you have identified. We should consider three things: transfer

activity, reconstruction activity, and write other description.

f.

Stage 6

In this stage, we should go back to

the input. If possible, try what we have made to the students then ask to

ourselves, can it be revised?

g.

Stage 7

In this stage, we should go back from

stage 1 until 6 with the revision we have. Analyze again from stage 1. The

revision can bring good improvements, such as: having new task, the original

task is useful too, having a number of exercises, having a good realistic

setting to practice the material.

h.

Stage 8

We need to check new material against

syllabus and amend accordingly.

i.

Stage 9

Here we try the material in the

classroom.

j.

Stage 10

In using the material in the

classroom, we can revise it for the further development. There’s no such thing

as a perfect material, a revision is always needed.

Thank you

BalasHapusWHAT IS EXERCISE AND TASK DESIGN IN ESP?

BalasHapusHow to design materials?

BalasHapusSu arıtma Servisi

BalasHapusSu arıtma servis